Sharing stories: practice and research presentation

In April 2025, Professor Anna Lise Gordon, Co-director of the Centre of Wellbeing in Education at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, and I presented at the Pedagogy in Action Conference organised and hosted by Dr Viki Veale and Christine Edwards-Leis on behalf of the University’s Pedagogy Research Special Interest Group.

The conference provided opportunity to be with others in education who are passionate about research and practice by engaging with and responding to the ever-changing educational landscape. The title of this year’s conference was: Sharing Stories: Practice and Research and it was an honour to be given the opportunity to present my personal story on how schools can support bereaved children alongside Anna Lise with all her research and passion to make a real difference to schools and teachers though policy, curriculum and research-led expert training for staff already in the profession and as a compulsory part of initial teacher training.

Listen to my talk or read my script, both available alongside my slides below.

Let me know what you think! Email: emma@themarfleetfoundation.org

My name is Emma.

I am a teacher. My last post was as Deputy Head of a primary school in Camden, North London.

I am a mother. I have 3 sons: Daniel is 14, Matthew is 12 and Sam is 9.

I am a widow.

My husband, Tom was diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer when he was only 39 years-old. Our sons were then 5, 3 and I was 37 weeks pregnant with our youngest. Tom lived with his cancer for three and a half years, but died in the summer of 2019 at Princess Alice Hospice, Surrey. Our sons were then 8, 6 and 3 years-old.

Since that summer of 2019, I have learned a lot about grief. About my grief, and about each of my boys’ as we each learn to live without Tom.

I am passionate about education and felt that something I could do to help my boys was to work with their school on how to best support their needs following the death of their dad.

This work led to creating The Marfleet Foundation in Tom’s memory. We provide training, resources and stories of lived experiences that reassure and empower schools to know what to do when there is a bereavement in their community. All with the aim to help bereaved children not only understand their grief but also to thrive.

I began this journey by exploring what grief is like for very young children. I took notice of and reflected on each of my boys’ experiences. I read research on childhood bereavement from child bereavement charities and I worked closely with the team of social workers who supported my family before and after Tom’s death at Princess Alice Hospice.

My first slide shows common feelings a child aged 3-7 experiences after the death of a close loved one and what they are beginning to understand about death in this age bracket.

Children grieve differently depending on their stage of development, their personality, their life experiences to date, and also depending on both the recovery environment they are in, and the responses they are exposed to around the time of bereavement.

Knowing this foundation of grief will help an educator in school meet a bereaved child where they are in both their understanding on death and the feelings they are experiencing. Both change and develop over time, but knowing the child and these foundations of grief will better equip educators to know what to do to best support that child’s bereavement specific needs.

My next slide shows possible behaviours a young bereaved child may present at school. Knowing what children understand about death and how they feel about grief at this age will help an educator better interpret these possible behaviours.

It’s important to ask: What is the child telling me?

For example, a newly bereaved child may tell you that they have a tummy ache. This may be a worry presenting as a body-centred reaction to their grief. They many need reassurance that the worry is a normal part of the grieving process. They may need a coping strategy that you can help them with. They may need your help to tell their family what they are worried about.

Another example is when a newly bereaved child’s reaction after a playground fall seems out of their normal, an out of proportion reaction to a situation. It may be that tears starting from a small injury become tears of grief. The floodgates have opened, and the child needs more than a physical clean up. They may need time with a trusted adult and space to talk about how they feel emotionally.

How a young child responds to grief is often described a puddle jumping. One minute they are overcome by strong feelings of missing their loved one and the next, they’re asking what’s for tea or whether they can play outside. Puddle jumping was certainly part of my children’s bereavement process. It’s a coping strategy for the big emotions and feelings of overwhelming grief.

So, How can schools support bereaved children?

I believe it is through both Proactive Planning and Reactive Care. This slide shows a few bullet points on what Proactive Planning and Reactive Care may look like in schools. I’d like to give an example of each.

Proactive Planning is when you know you will teach a lesson or deliver an assembly that may be difficult for a bereaved child because it links to their bereavement story or is about death. My example is on a book as a class reader which includes the death of a main character. Think: Charlotte’s Web by the E.B. White where the death of a character is written about so beautifully. I am in no way saying that books which include the death of a character should be removed from the curriculum. I am saying the opposite!: Keep those books, lessons and assemblies which feature loss, change, death and grief, because they very much help all children, those bereaved and of course those - all of us - who one day will be bereaved too. It’s about supporting a bereaved child in those school situations with what I like to call a lifeline.

Examples of lifelines an educator may provide a bereaved child with for my example of a class read when a character dies could be:

Prepare the child and family beforehand - so there are no surprises in the lesson

Timetable the lesson before a playtime - so they can talk to you after a lesson instead of going straight out to play, lunch, home or into another lesson

Consider having extra adult support - for the adult delivering the session or to have extra eyes on a bereaved child in case further support is needed

Prepare all the children in the class for a read about death and set the appropriate tone to support them all

Consider how best to deliver the story in a way that supports the needs of all children, for example as an adult led read and an adult led discussion focusing on why the death was part of the story’s narrative

And finally, consider carefully how to close a session like this so that all children feel supported and ready to continue with their school day

Reactive Care is about all those moments you have not planned for. They are the moments when your response matters. It’s about acknowledging a bereaved child’s experience and reassuring them.

My example is the picture on the slide. Sam was asked to draw his family when he was in Nursery. He was 3 years-old and his dad had died 3 months earlier. He has drawn himself, his 2 brothers, me and his dad.

How his teacher responded to seeing this picture mattered. I believe Sam was asking whether his dad was still in his family even though he had died and whether is was ok to draw him. I was so pleased that Sam’s teacher reacted with care and acknowledged Sam’s experience. They told Sam that they liked his picture and asked him if he’d like to tell them about it. They gave Sam time to talk about his family. They gave Sam time to talk about his dad. And, they also gave me his picture and told me this story which meant so much to me. I knew that he was in a place where his bereavement would be supported and I had a picture to treasure.

My boys’ junior school took their support to the next level to meet a need in the school. Matthew’s Year 3 class had 2 children whose dads had died, and one child whose baby sibling had died. The school wanted to do something more, something more specific, to support them in their bereavement.

So the school’s family support worker set up a bereavement group. These children met with her in the Nurture Room once every half term, unless there was a need for a more frequent get together. They seemed to eat a lot of mini Colin the Caterpillar cakes in these sessions… but it was about a lot more! It was time out of their regular school routine to be in a safe and nurturing space with a trusted and nurturing adult. She wasn’t a specialist bereavement expert or councillor, but she knew the children and their families, and what they had experienced with the death of their loved ones.

In these sessions, the children shared their feelings - perhaps an anniversary or an occasion such as Father’s Day was coming up. They shared memories of their loved ones - continuing to build on the ever changing relationship they will always have with them. And they discussed coping strategies for when things in life become difficult for them, triggering their grief.

These sessions meant that the school would know what the children may be worried about, for example if an assembly was coming up for Remembrance Day, and they could put supportive measures in place to help them.

I believe the children themselves have benefitted so much by having had these regular group sessions focused on their bereavement specific needs for 4 years - the children are now at secondary school but those feelings and memories shared and those coping strategies explored with one another over their junior years, have secured foundations on which to continue building good mental health and wellbeing for their futures.

I have created guided activity plans for groups such as this which can be downloaded from my website. Each one starts with a book as inspiration for a supported conversation with a bereaved child or group of children. I include support notes for the adult leading the session and key questions they can use to guide the threads of conversation. There is then an accompanying activity or craft on each one which builds on the central theme of the book and allows the children time to talk, share and express how they are feeling in a safe space.

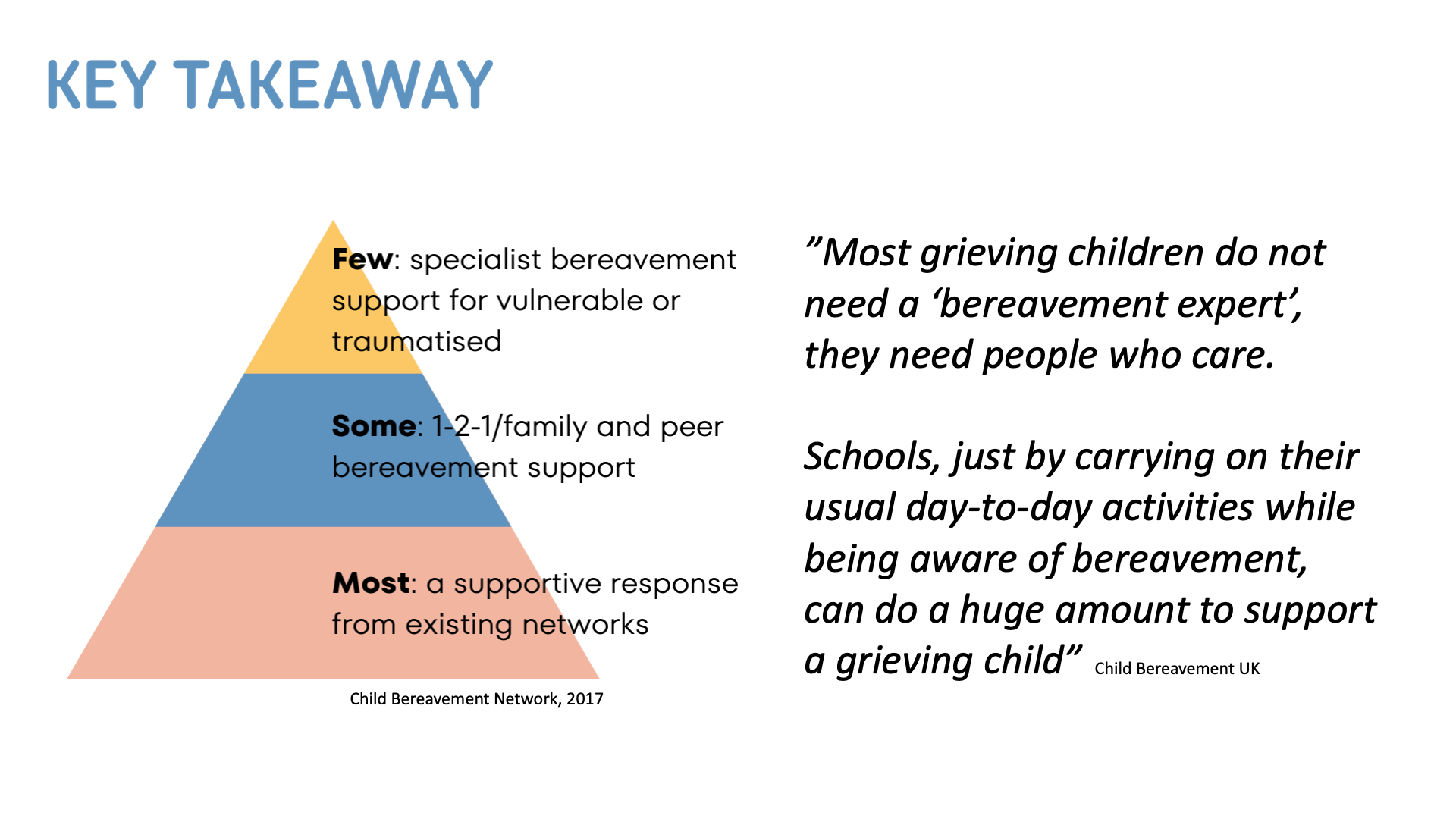

My last slide is the key takeaway from this presentation.

On the left hand side is a diagram of a triangle taken from Child Bereavement Network. It shows from research what they consider good support for bereaved children looks like. The bottom largest section of the triangle says that most children need, “a supportive response from existing networks” of which school is a large part.

The quote on the right hand side comes from Child Bereavement UK and can be found on their support for schools webpage: “Most grieving children do not need a ‘bereavement expert’, they need people who care. Schools, just by carrying on their usual day-to-day activities while being aware of the bereavement, can do a huge amount to support a grieving child.” It’s where the school shows their awareness of the bereavement which makes all the difference to a bereaved child.

So… Hope is not a strategy. Have a plan.

Put a Bereavement Policy as a living document in place. A break-glass moment to support you to know what to do when there is a death in the school community.

Include death education and literacy into your school curriculum to support all children who will one day be bereaved. Death is a part of life. For bereaved children, look for where it already is and consider lifelines that will help them and you. This is proactive planning.

Train your staff to be able to talk about death with children. Research-informed expert training on how to support bereaved children in school will reassure and empower school staff know how best to help bereaved children not only understand their grief, but will allow them to thrive.